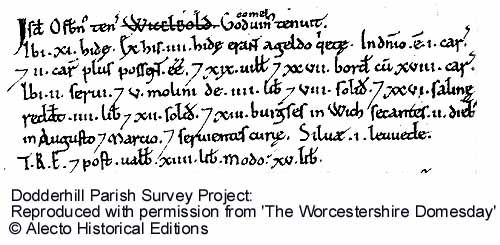

The Domesday Entry for Wychbold

A Translation of the Domesday Book Entry for Wychbold

THE DOMESDAY BOOK ENTRY FOR WYCHBOLD

(translated by Dodderhill Parish Survey Project)

Folio 176 d, chapter 19 para 12

“LAND OF OSBERN SON OF RICHARD

“IN CLENT HUNDRED

“The same Osbern holds Wychbold. Earl Godwin held it. [space for more information, left blank]

There are 11 hides. Of these 4 hides were free of tax. In the demesne is 1 plough

and 2 ploughs more would be possible and [there are] 19 villagers and 27 bordars to whom [belong] 18 ploughs.

There are 2 slaves and 5 mills worth £4 and 8 shillings and 26 brine-shares which yield £4 and 12 shillings and 13 burgesses in Droitwich [who are] cutting for 2 days in August and March and serving the court. [There is] woodland [measuring] one league.

In the time of King Edward and afterwards it was worth £14. Now [it is worth] £15.”

EXPLANATORY NOTES:

“Osbern son of Richard” was the ‘owner’ or chief tenant of the manor. His father ‘Richard’ was the lord of Richard’s Castle in Herefordshire, Richard Scrope, who seems to have settled there before the Norman Conquest. His surname is an Anglo-Norse nickname but he was Norman, and passed his lands on to his son.

“Earl Godwin” was the father of both Harold (who in 1066 led the Saxons against William ‘the Bastard’ of Normandy at Hastings and lost, allowing William to become ‘the Conqueror’ and William I of England, the first Norman king) and of Edith, wife of Edward the Confessor, last Saxon king of England whose death, childless, earlier in 1066 had initiated the crisis leading to William’s invasion of the country. Earl Godwin was one of the most powerful people in the Saxon kingdom of England; Wychbold was one of his many estates and it is not known if he ever visited it. Given the importance of the estate – that is, it included the brine springs of Upwich which generated great income – it is not surprising that it was held from the King by such an important magnate.

“Hide” – the hide was a way of assessing the value of a manor for its tax liability, and also notionally a unit of land measurement, indicating both the productivity and the tax liability, and is thought to be the amount of land which could support a family for a year. A standard hide is said to be 120 acres but in practice the extent of a hide varied enormously, and where other resources existed which were more productive than arable land (such as woodland, fishing, fowling, or pasture which was used for sheep), the actual area of the land could be much smaller than the area implied by the number of hides used for its tax assessment. It is possible that the value of the salt rights held by the manor [see “brine-shares” entry] has also been taken into account in the valuation of the manor at 11 hides.

“4 were free of tax” – this indicates that an area of land and/or other resources was owned by a person or institution who did not pay tax. It is probable that this represents the holding of the Saxon ‘royal villa’ and/or of the minster church (St Augustine’s).

“Demesne” was the Lord’s own land within the manor, worked by the labour of the people who lived on the manor as their ‘dues’ to their Lord; this would have been managed by a bailiff or local steward on behalf of the Lord of the manor.

“Plough” would refer to a plough drawn by 8 oxen, which has implications both for the amount and quality of land (a team of 8 oxen drawing a plough could plough an acre of good arable land in a morning) but also because of the need to feed oxen over the winter, which required natural hay-producing meadow land as at this time no grass was sown and no winter roots were planted. Meadow was both scarce and valuable at this time, as evidenced in the whole of Domesday Book.

“Villager [villein]” was an inhabitant who held a larger amount of land in the common fields, perhaps 15-30 acres. He was not free to leave the manor, but some villagers in Domesday could afford to rent whole manors or fisheries. He would have to do some work on the Lord’s land as well as cultivating his own.

“Bordar [bordarius]” was an inhabitant who held a smaller amount of land in the common fields, perhaps 5 acres. He was not free to leave the manor. Bordars were sometimes freed slaves, and they would have had to do more work on the Lord’s land than a villager. Like a villager the bordar would have time to cultivate his own land, and to work for pay on the land of other men where the opportunity arose.

“Slaves [servi]” were the lowest level of inhabitant, regarded more as an object rather than a person, who did the majority of the work on the demesne land. Ploughing would have been their main occupation there, with two men required to operate the plough team – so 2 slaves for the 1 plough on the demesne land of Wychbold makes sense. However a slave had some free time, in which he could work for pay; he might even save money to buy his freedom. He may have had a small amount of land allocated, and did have an annual allowance of food. It is thought that Domesday Book under-records the total number of slaves; the 2 slaves recorded here may have each have been the senior male of a family, with dependents (including those old enough to work) simply not recorded.

“5 mills” is an unusually large number in one manor and is the second largest concentration in the county at this time. The most likely locations for these mills in the 11th century are the sites of Paper Mill (at the end of Paper Mill Lane – originally a corn mill), the first Wychbold Mill (at the end of Mill Lane, south side), Impney Mill, Briar Mill, and the Droitwich town mill (which was a detached part of Dodderhill parish into the 19th century), all on the River Salwarpe.

For more information on the mills of Wychbold click here

“26 brine-shares [salinae]” refers to a defined volume of brine from the Droitwich brine pits (from the Upwich brine pit, in the south of the manor), which would be boiled to evaporate the water and produce salt. Each share was 6912 gallons in a year, which at just over 2.5 lbs of salt from a gallon produced 8 tons or 320 bushels of salt, so Wychbold had 208 tons of salt each year. While some of this would have been used on the manor, and earlier also at the Saxon ‘royal villa’, it is likely that most of this remained in Droitwich, which held markets for the bulk selling of the salt produced there, and was sold on to produce income for the manor’s owner. The amount quoted, £4 12s, was the tax payable on this ‘income stream’, not the value of the salt itself – that would have been higher. (“Salinae” is often translated as ‘salt houses’, meaning the small industrial sheds in which brine was boiled to make salt, and it is possible that there was one salt-house near the Upwich pit to boil each share of brine. However as Domesday Book’s prime purpose is to list tax assessments, it seems more appropriate to see “salinae” here as referring to the brine which generated the wealth which was taxed.)

“Burgesses” are citizens or freemen of a borough, and often a member of the governing body of the town or borough, so the medieval equivalent of a town councillor. In other boroughs they owned property and ran businesses, but in Droitwich we know from later records that to be a burgess meant owning rights to brine shares, and these rights were passed on only by marriage and inheritance. The burgesses mentioned here are Droitwich burgesses who, certainly from 1215 (King John’s charter) and probably for some time before then, governed the affairs of the town and particularly the regulation of the salt industry. They were probably also salt-makers themselves, processing the brine shares to which the owners of their places of residence were entitled. Domesday Book records 89 burgesses in Droitwich itself, 4 in Salwarpe, 7 in Witton and these 13 in Wychbold, making a sub-total of 113 in or very near Droitwich; a further 3 are recorded (1 each in Crowle, Cookhill and Morton Underhill), giving a total of 116 burgesses at this time. The Wychbold group is the next largest total after those stated to be in Droitwich, and this may reflect the earlier situation of ownership of the main Upwich brine pit by the kings who used the Saxon ‘royal villa’. By the time of Domesday book, and no doubt before that, the existence of burgesses suggests Droitwich is separately established with some self-government as a ‘borough’ which functioned like other towns but also gained from the production and marketing of salt by providing labour and supplies and the location for the markets.

“cutting for 2 days in August and March and serving the court” is one of the most enigmatic parts of the information given. “Secantes” is often translated ‘reaping’ but the literal meaning is ‘cutting’ and this might make more sense for the days in March as there is not much to ‘reap’ or harvest. However, hazel withies are cut in March, and we know from archaeological excavation that the baskets used for the collection, drainage, and transportation of salt produced near the Upwich pit were made of hazel, so it is probable that the activity referred to is the cutting of hazel withies in order to make these conical baskets. The days in August could have been for normal reaping or even mowing, as evidenced elsewhere in Domesday Book; this was during the main six-month salt-making season known from later references. Alternatively, the burgesses could have been engaged in March on cutting the ‘young pole wood’ [straight young growth of either 4 or 8 years age from managed woodland] needed in large quantities as fuel in salt production, carried out from June to December. It is strange that only this short time (2 or 4 days at most) is recorded on these activities, when it is likely that most of the inhabitants of the parish and its neighbours would have spent a lot of time reaping or mowing, cutting withies, and cutting wood; it is therefore likely that the short time period mentioned is connected with the other part of the entry, serving the court, so this is a specific reference to these activities being undertaken for that short time as duties connected with service at the Saxon ‘royal villa’ while it was functioning as the estate centre. (It is presumed that by the time of Domesday Book the ‘royal villa’ no longer existed as a functioning centre or ‘court’. These duties were however still remembered and recorded separately, and in that way seem to have some continuity into the Norman period.) The burgesses, like the other inhabitants of the manor, would no doubt have spent a lot more time on some or all of these activities but did so separately from their ‘service to the court’. [There are other examples in Domesday Book of short periods of service on reaping or mowing being recorded where these seem to have been specific duties related to an identified person or type of person doing the work, and/or to the work being a customary duty because of holding a particular piece of land, and this situation must go back to before the Norman Conquest. Perhaps this is also the case with the Wychbold burgesses because their predecessors used to ‘serve the court’ and were therefore an identifiably separate type of tenant.]

“Woodland [measuring] one league” is difficult to interpret as the word used, “levvede”, seems to be meant in Worcestershire entries as a measure of area but it is not clear how great that is. League (“leuga”, “levve”) as a measure of length is thought to be one and a half miles but again in Worcestershire could be only two-thirds of a mile. Using a formula developed in the 1970s to analyse Domesday Book woodland references, which assumes the league to be 1.5 miles and the area to be half as wide as the given length, the Wychbold woodland might equate to 504 acres of woodland (approx 218 ha). The area of Dodderhill parish most likely to be wooded is the long triangular piece to the east, leading up to Dodderhill common/Piper’s Wood, and amazingly this covers 509 acres by modern measurement, so could easily have been the ‘one league’ mentioned in Domesday Book. The woodland would have been managed or ‘farmed’, with trees coppiced (cut off near the ground) or pollarded (cut back at about 2 metres above ground) every 4 or 8 years so that the tree produced new growth of multiple straight shoots which thickened into ‘pole wood’ that was easy to cut, transport and use as fuel. It has been estimated that between 4 and 5 acres of managed woodland are needed to produce enough fuel to make one ton of salt per year, so the woodland within the manor would not be sufficient fuel to make the 208 tons of salt that Wychbold’s share of brine generated annually; we can assume that other sources of wood were needed. The importance of woodland for the salt industry is evidenced by the entry for Droitwich itself in Domesday Book, where the Sheriff of the county states that ‘if he does not have the woodland, he cannot pay [the tax due, 65 pounds of silver by weight and 2 measures of salt] in any way’.

“In the time of King Edward [in Latin, tempore regi Edwardi, or T.R.E. for short]” refers to the pre-Conquest years before 1066. Domesday Book gives valuations for the tax due from each manor at up to 3 time periods: the time of King Edward, afterwards (ie between 1066 and the time of Domesday Book), and now, 1086 when the Domesday Book survey is compiled. The value of Wychbold has increased, in contrast to other manors or estates whose value is less in 1086 than it was previously. From this it can be assumed that salt production continued more or less uninterrupted through the post-Conquest period.